To understand the food and beverage traditions that Oregonians and those of us in Lane County enjoy today, take a few steps back in time. Years before the crops we now enjoy were established in the state, Oregon’s first foods that nourished our native population included salmon and mussels, deer and elk, camas roots, and wild berries like huckleberry. While camas isn’t common on menus, the rest of those foods can certainly be found on local tables. Oregon is also known for blueberries, marionberries, Dungeness crab, and hazelnuts. We have well-established traditions of beer, distilled spirits, kombucha, and non-alcoholic beverages including juices (Genesis Juice has been made here since 1975!). And we are on the world stage for wine. For years, Oregon has been known for its pinot noir, but now chardonnay is taking hold as well.

1948 – The marionberry was developed in Corvallis in 1948 by Dr. George Waldo, and is grown exclusively in Oregon.

Oregon’s pear orchards were established by two travelers of the Oregon Trail, Henderson Luelling and William Meek. In 1847, Luelling brought over a wagon full of fruit trees, and together they started an orchard near what would become Milwaukee. Farther south and a bit later, in 1914 near Medford, Samuel Rosenberg’s sons, Harry and David, developed 240 acres of Comice pears. The pear tradition certainly lives on in the spirits produced by Clear Creek Distillery, one of the first craft distillers in the country, from Bartlett pears grown in the Hood River Valley.

Hops In The Willamette Valley

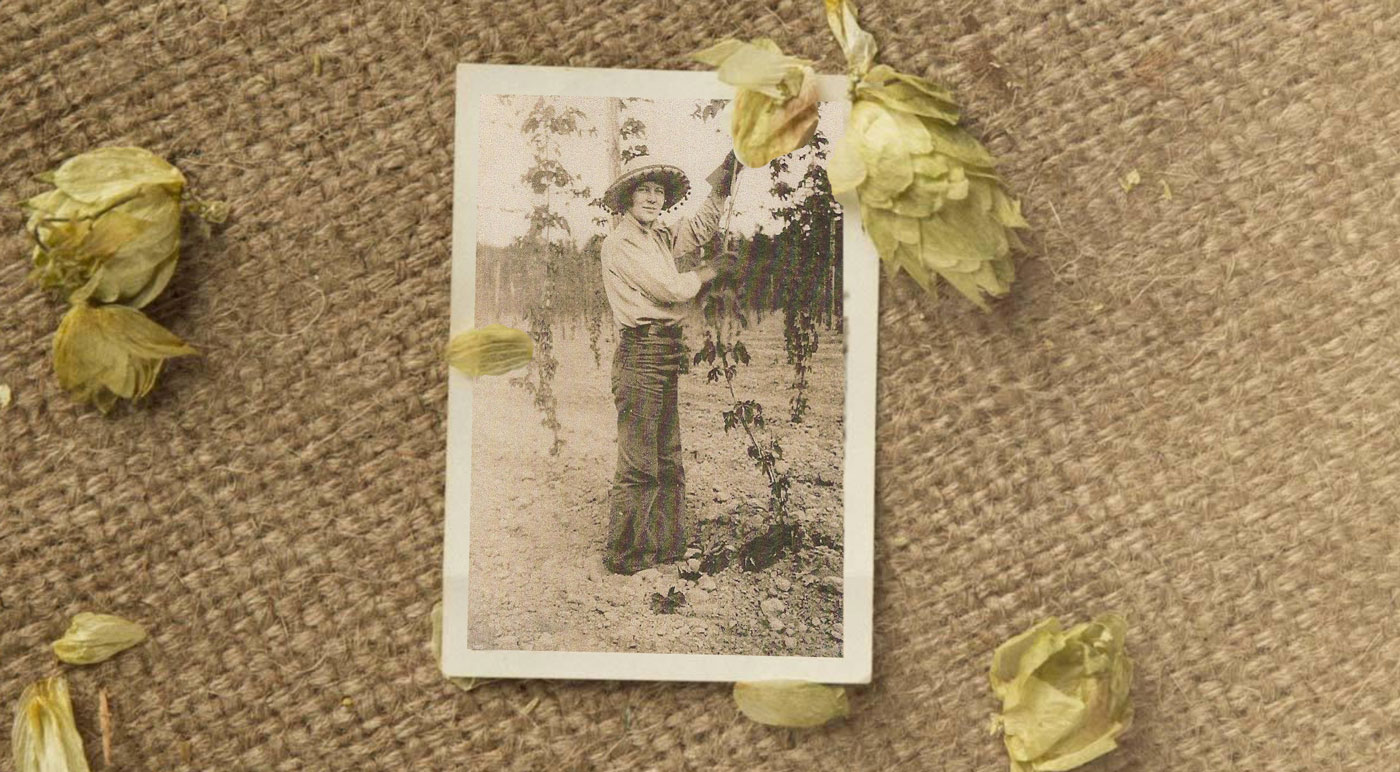

The first hops grown in the Pacific Northwest were grown in Oregon. Though there are different origin stories, hops first appeared in the Willamette Valley in the mid-1800s. Hops were likely brought here by farmers, who could have used them medicinally or to make a starter for bread. They also may have arrived in 1844 with the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, who came to Oregon from Belgium and established a school in St. Paul until 1852.

In Lane County, we credit George Leasure for planting the first European hop varieties. His farm, in what was then called Eugene City, was adjacent to a land claim owned by Eugene Skinner, Eugene’s founder. By the early 1900s, Oregon was the top state in the nation for hop growing. History shows that there were about 200 hop growers from Junction City to Cottage Grove, including a large field owned by Alexander Seavey, the namesake of Seavey Loop near the base of Mt. Pisgah.

Prohibition threw a little bit of a wrench in our beer history. In 1914, years before Prohibition was enacted nationally on January 17, 1920, voters of Oregon passed an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting the manufacture, sale, or advertisement of intoxicating liquor. One could argue that the non-alcoholic drink movement so popular today had its origins in this time. Oregon’s state archives describe businesses sprouting up in order to create non-alcoholic drinks that sounded like alcoholic beverages: Ras-Porter, Graport, Loganport, and Cherriport, for example, made by Henry Weinhard, founder of Oregon’s second beer brewery. The brewery still makes sodas, although Henry Weinhard’s Private Reserve, the brand that helped pave the way for Oregon to become a craft brewing superstar, was discontinued by parent company Molson Coors in 2021. (Hop Valley, also owned by Molson Coors, revived the namesake beer in 2022.)

2022 – Oregon farmers harvested 7,756 acres of hops at a yield of 1,728 pounds per acre, at $6.35 a pound.

Hop farming is not easy, but it is easy to spot from the road: The little cone-like hops clusters grow on vines (technically called “bines”) that can grow up to 25 feet and are trained to climb up trellises. Hand-picking usually means cutting the vines at the bottom and laying them down, although machinery can do the job now. In the old days, the vines were unhooked from the trellises using long poles, then the cones were hand-picked and weighed. “Dirty hop pickers” were ones that used unethical means (stones and other debris, for instance) to make their bags weigh more. The bagged-up hops were loaded up on wagons and taken to hop kilns — small square buildings with conical tops — for drying.

The September 1963 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly has an article called “The Vanishing Hop-Driers of the Willamette Valley.” It says: “Fast disappearing from the Oregon landscape are the picturesque hop driers that formerly could be seen on hundreds of hop farms in the Willamette Valley.” On a tour from Portland to Eugene, one could see these square barns every few miles, either single ones or clusters of four, six, or eight, with their chimney-like ventilators reading above the hop fields or the trees.

If you want to experience the agricultural scenery of a modern-day hop farm, along with the beers which take their flavor and aroma from the crop, visit TopWire Hop Project in Woodburn. Opened in 2020, the beer garden is located at Crosby Hop Farm, a 600-acre fifth-generation hop operation. The tap list includes beers from around the country that use Crosby hops, as well as other beers you know and love.

Erica Lorentz is a fourth-generation hop farmer at Sodbuster Farms in Salem. They’ve done business with many breweries across the state, including McMenamins, which sends brewers out each year in September for a “Running of the Brewers.” “They get their bag of hops, and they run to their car and go directly to the brewery and put those hops in the kettle the same day that they’re picked,” says Lorentz. “The growth of the craft brew scene meant that we were no longer dealing with giant hop buyers but brewers that could come to the farm, smell the hops, and pick what they wanted.”

Today, the Eugene beer scene has grown tremendously. The city has dozens of beer halls, from on-site breweries like ColdFire and Gratitude Brewing to bottle shops and pubs like The Bier Stein and 16 Tons, plus growler fill stations like A Beer Club. Some of our oldest microbreweries, like Steelhead, are still pouring. Ninkasi Brewing, which opened in 2006, is distributed from California and Oregon to Virginia. Alesong Brewery consistently wins awards for their barrel-aged beers. In the 2023 Oregon Beer Awards, Alesong walked home with a gold medal for Raspberry Parliament and a bronze for Señor Rhino in the barrel-aged-stout category. And our newest breweries, with more on the way, have exciting menus too. Xicha Brewing, a Latinx-owned brewery, expanded from its original location in Salem and also features a delicious nuevo Latino restaurant with tacos and tequila. Drop Bear Brewery (named after a mythical carnivorous koala from Australian folklore) has pizza and a Thai food cart, along with an “Xperimental” tap where they pour something unique and interesting. The Old 99 Brewery has been working on their space in front of Albertson’s on West 18th for the past few months.

Options for cider drinkers have grown enormously, too, with WildCraft Ciderworks and Elkhorn Brewery and Ciderhouse making loads of ciders that go far beyond apple. WildCraft is known for its ciders made from 100% Oregon-grown fruits, particularly from heritage orchards, fermented with natural yeasts. Elkhorn’s cider list includes blood orange, raspberry, and pomegranate flavors.

The state fruit is the pear, and Oregon produces about 800 million pears annually, or nearly one in three of the country’s pears, second only to Washington.

Mead is no longer the only fermented honey drink on the market. Viking Braggot Company is the only brewery to offer a full line of braggots, which are one of the oldest fermented drinks. Consider it like a beer brewed with malts and honey. You can really taste the honey along with other botanicals or grains, like rye, that they use in the mix — and you don’t have to be a Viking to enjoy it!

Why We Love Willamette Valley Grapes

An early generation of winemakers, the experts who were supposed to know what they were talking about, said that Oregon wines just wouldn’t work. Oregon was too cold, too wet, to ripen good fruit. It’s true that when the University of California at Davis enologists were espousing this untruth in the 1950s, there was little precedent for Oregon being a wine-growing area. Little precedent — but not none.

That Oregon Trail pioneer Henderson Luelling I mentioned before also brought grape vine cuttings with him. In 1852, Peter Britt started making wine in Jacksonville. (Oregon became a state in 1859.) The Reuter family, who lived where David Hill Winery now stands in Forest Grove, won either a silver or a gold for their wine at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 — the historical record doesn’t agree on which medal he brought home. But the facts are clear that Oregon wine has always been award-winning, even if the rest of the world wasn’t paying attention.

In 1963, Richard Sommer’s HillCrest label introduced Oregon riesling. And David Lett released his first pinot noir from Eyrie Vineyards in Dundee in 1970. The world started noticing Oregon wines in 1979, when Lett brought his Eyrie pinot noir to a blind tasting at the Gault Millau tasting in Paris. The wine placed third among the best in the world. But the tasting panel thought it might be a fluke so they called for a rematch the next year. Eyrie placed second. It clearly was no fluke. “I’d always thought that we could do better than Burgundy,” David Lett was quoted as saying at the time. “This was my chance to give it a try.”

Established in December 2021, Oregon’s newest wine-growing American Viticultural Area (AVA) is the Lower Long Tom, also the southernmost AVA in the Willamette Valley.

Many of today’s wineries have legacies that go back long before their current names. In 1972, Lee Smith established Forgeron, which became LaVelle Vineyards, still family owned and making estate-grown pinot noir, among other varietals. Doyle Hinman launched Hinman Vineyards near Veneta in 1972, and in 1993 Carolyn Chambers purchased the winery and rebranded it as Silvan Ridge. “Silvan Ridge Winery is the original winery for the Eugene area, and one of the pioneers in the industry as a whole in Oregon, so we see ourselves as very connected to Oregon’s wine heritage,” says Angela Jaquette, manager of Silvan Ridge Winery, Elizabeth’s Wine Lounge, and Elizabeth Chambers Cellar. They are on the forefront of Oregon wineries producing a unique style of chardonnay that contrasts with the typical “California” style.

Grapes for wine are Oregon’s 8th top agricultural commodity, according to the USDA. No. 1 is greenhouse and nursery items.

“Chardonnay is definitely a part of Oregon’s white wine present and future,” says Jaquette. “Silvan Ridge will begin producing a chardonnay with the 2023 vintage, and Elizabeth Chambers Cellar has been producing two chardonnay wines for several years now. Both of the Elizabeth Chambers Cellar chardonnays are great examples of what Oregon can do with this varietal.”

Today, there are about 900 wineries in Oregon, including some 700 wineries in the Willamette Valley and about 70 in and around Lane County. Indeed, exploring nothing but Oregon wines could be a hobby for the rest of your life, to immense satisfaction. Start with one of Lane County’s newest wineries, 514 Vineyards, on Territorial Highway, making wines from vines planted from 1998 through 2016. Winemaker Drew Voit has a long history in the Willamette Valley, crafting wine for Domaine Serene and Willamette Valley Vineyards in years past, plus Sylvan Ridge Winery and Elizabeth Chambers Cellars.

King Estate Winery, also on Territorial Highway, is the largest biodynamic-certified vineyard in North America. Already large at more than 1,000 acres, King Estate is expanding after recently purchasing Pfeiffer Vineyards and converting that vineyard to biodynamic status. They also grow fruits and vegetables on 24 acres of gardens that supply their on-site farm-to-table restaurant and local food pantries.

Bennett Vineyards & Wine Co., an 85-acre winery in Cheshire open since 2008, exclusively grows pinot noir and makes wine in the style of France’s great burgundies – the ones that the Gault Millau tasters were expecting. Iris Vineyards recently made history when it opened the first wine tasting room that Springfield has ever had.

Distilling Has Its Day

Distilling is one of the newest industries to sprout up from Oregon’s soil. There are dozens of distillers in the greater Portland area, and in Lane County, we get to enjoy distilleries that have entered the world stage within just a few short years. After opening the award-winning Swallowtail Spirits Distillery in 2014. Kevin Barret’s vodka received a double gold medal at the 2017 Seattle International Spirits competition, and his Navy Strength Gin won gold in Seattle and New York international competitions.

At Thinking Tree Spirits, distiller Kaylon McAlister left a career at the University of Oregon as an archaeologist to follow his dream of making spirits. He says Thinking Tree is “community powered.” “Everything we make has some connection to this community,” he says. Lavender is grown by an employee. Honey is sourced from local bees. A self-proclaimed “science nerd,” McAlister created a pea-flower vodka with a light purple hue that changes color when it’s mixed with cocktail ingredients. McAlister’s Big Adventure barrel-aged gin and Whiteaker Solera barrel-aged rum both won platinum awards at the Best of the Northwest spirits competition in 2022.

Elixir Craft Spirits’ Fête Vodka with pure gold flakes won double gold in that same competition. Explore Elixir, founded in 2018 by Italian brothers Andrea and Mario Loreto in Eugene, if you want a hand-crafted amaro for sipping neat. Their Calisaya, made with cinchona bark and botanicals, follows a centuries-old Italian tradition of botanical amaros. Andrea Loreto started playing with botanical infusions from his Italian grandmother’s old recipe books. “My brother and I tried the Calisaya recipe and thought it was very good,” he says. “It’s a great substitute for Campari, works very well in all kinds of cocktails like a Negroni or a Boulevardier, or it’s very good by itself also.”

Another popular and unique liqueur they create is Iris, which also comes from an old Italian recipe. “It’s made from the rhizome of the iris flower,” he says, a plant which covers the Tuscan hills each May. “It’s got a very floral scent like a blue flower, and a violet flavor, but it is also zesty. I think I am the only one that uses it as a main ingredient in a spirit, but it also works great on its own or in a cocktail.”

In 2022, there were 720,000 acres of wheat harvested in Oregon.

Crescendo Spirits, which has been making liqueurs from organic lemons, limes, oranges, and grapefruits since 2013, has recently rebranded as Fireside Distillers. Their new tasting room opened to the public in May, and while you can get some of their organic spirits at Costco and local liquor stores, some of founder Kyle Akin’s products are only available on-site. If you create your own artisan spirits, tinctures, or herbal extracts, Fireside’s Diamond Clear is a 190-proof spirit made from organic cane sugar.

Heritage Distilling Company got its start locally in 2011. It is now the largest independently owned craft distillery in the Pacific Northwest, with six distillery tasting rooms in Washington and Oregon.

Zero-proof

Whether you don’t drink at all or drink less, there are numerous new and exciting non-alcoholic options. Juices, kombucha, jun, tonics, buzzless beers, and more are on the scene now. BNF Kombucha flavors include mango marigold, peach rose, grape lavender, Oregon blueberry, and lots more.

You can trust the most well-stocked drink coolers in town, at The Bier Stein, to have a good variety of non-alcoholic beverages, including sodas from around the world. Market of Choice is another great spot, thanks to their curated collection of zero-proof beverages and mixers, many from local producers.

High Street Tonics got its start in the spring of 2021 when Cheri Hammons began preparing tinctures and oxymels. The tonics are health-conscious on their own, but by mixing them with other local non-alcoholic liquors like those from Hood River-based Wilderton, you can create delightful cocktails that are inherently non-alcoholic but just as satisfying.

“The bitters are alcohol-based extracts and the tonics are honey and apple cider vinegar–based and are a lot like a shrub or syrup and used in the same way in drinks,” explains Hammons, who mixes and serves her zero-proof cocktails at pop-up counters. “Everything is made using locally sourced ingredients.” Hammons gets all the herbs she uses from Mountain Rose Herbs in Eugene, the honey and vinegar from Eugene’s Hummingbird Wholesale, and organic cane alcohol from Organic Alcohol Co. in Ashland. “We love collaborating with other local businesses to create unique non-alcoholic menu items, especially when using their locally grown or locally crafted ingredients,” she says.

You can think of the bitters and tonics as allies to support your wellness, but they can also just turn water, juice, or tea into a delicious and more layered drink. “The herbal ingredients we use impart complex flavors while also offering nutritive properties,” she says. “When making a non-alcoholic cocktail, it’s the experience of mixing the flavors and partaking in that ritual of having a drink after work or with dinner — without having to alter their state — that people are craving”

Have a Cup of Tea

Tea is growing in popularity — the first Eugene Tea Festival took place in May, organized by Madelaine Au, the operations manager at Young Mountain Tea. Young Mountain Tea partners with farmers in the Himalayan region of Kumaon who are earning four times the industry average. Eugene has been home to J-Tea for years. A dream for the tea enthusiast, or for someone who wants to drink tea but doesn’t know how to find what they like, J-Tea’s tasting room demystifies the process. Angela McDonald, owner of Oregon Tea Traders, has promoted growing tea in Oregon and provides loose leaf teas and tea blends from all over the world.

Take It Home

Whether you sip a cup of local tea or juice, a pint of kombucha or beer, or a glass of wine or cider, you’re supporting a robust economy in Oregon, Lane County, and in Eugene. We’ve got some of the highest quality ingredients on the planet right here in our backyard, so whichever beverage you choose to drink at the end of the day or bring to your next cookout, you can’t make the wrong choice.