Jud Turner grew up in Eugene with a big backyard full of handcrafted forts, wooden rollercoasters, and any other projects his young mind could think up. With encouragement (and access to any tools needed) from his parents, Turner found his love for creating art.

“I learned early on to look at things around me for their alternative uses or interpretations and how I might repurpose something for my own fun,” Turner says.

After graduating from the University of Oregon with a bachelor’s degree in fine arts, Turner decided to focus on metal sculpture. He felt that 2D art was too precision-oriented for his creative desires.

“As a metal sculptor, I get to legally use fire, violence, and piracy in the name of ‘art’ and in ways that would get me in trouble in most other areas of life,” Turner says. “Combine these tendencies with a sense of beauty, sensuality, and a dash of the ridiculous, and I have an extremely ripe area to sow my art.”

Turner spends 40 to 50 hours per week at the studio working on numerous projects. His 160-pound pet pig, named Pigg, comes along and hangs out at the studio every day. When anxiety about work becomes overwhelming, Turner can spend a few minutes snuggling Pigg to relax.

“I spend more time with or near Pigg than any other creature, and he is keenly intelligent,” Turner says.

Working on multiple projects, all in different stages of creation, helps Turner stay motivated and inspired. The most exciting part of making a sculpture is the first half, he says. The second half requires more discipline and focus, and if self-doubt ever makes an appearance, it’s usually then.

“I never actually pull off the sculpture I imagine wanting to make—it’s more a game of ‘how close can I come this time?’” Turner says.

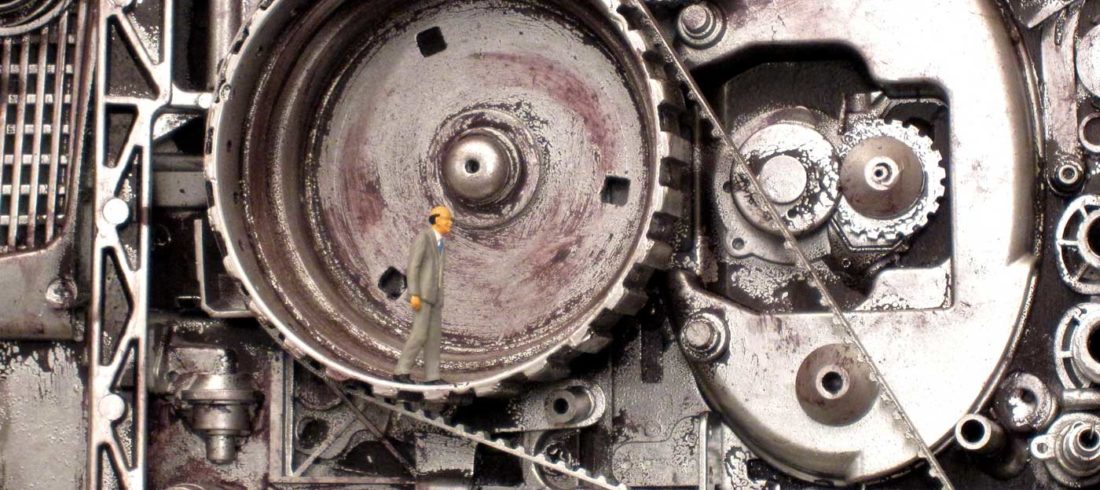

By welding and cutting pieces of found objects for his sculptures, Turner is able to add and remove pieces with ease. If a certain part or piece of a sculpture isn’t working, he is willing to strip the sculpture and start again.

“I have to be very self-critical,” he says.

Turner’s work has been featured locally, nationally, and internationally. His favorite pieces are ones where he can fold in a few layers of meaning under the surface. Living by the artistic philosophy that “between seeming contradictions lie greater truths,” Turner says he wants his sculptures to work on several levels with the viewer: always pleasing to the eye and always giving the mind “something to chew on.”

“I’ve always felt like humans divide things too simply into just two opposing categories—good or evil, black or white, right or wrong—and that we overlook a lot of the nuance and other possibilities, or miss the larger truths,” Turner says.

One example is his sculpture “Blind Eye Sees All (No Secrets Anymore),” which was purchased by Ripley’s Believe It or Not. The multimedia assemblage piece was created with cameras and lenses welded together, some containing a watching eyeball. Turner took the sculpture to the next level by having one of the cameras serve as a functioning security camera. Turner was even able to speak to viewers with the camera’s two-way microphone. Once a kid was poking at the sculpture, so Turner yelled, “Don’t touch me!”

“This may be why the login password was changed by Ripley’s staff,” he jokes. “[But] it truly added meaning to the piece.”

“This may be why the login password was changed by Ripley’s staff,” he jokes. “[But] it truly added meaning to the piece.”

Another example is “Factotum,” a piece constructed from old sewing machines, with the underlying theme of the repetitive labor some people have to do in order to make a living. Turner named this piece after the Charles Bukowski book that recounts the unattractive, low-wage jobs he had before his writing career.

Turner also uses irony to make difficult subject matter easier to approach, such as “The Thirteenth Skull.” In this piece, the 12 skulls encircling a mirror represent the hours on a clock, with the viewer’s own reflection making up the 13th skull. Another example is his “Watership Down” series, where rabbit sculptures are built out of dismantled rabbit traps.

Even after 25 years of sculpting, Turner still has many untouched ideas for his work. In his studio, he keeps a box filled with slips of paper with ideas from years past scribbled down, each hoping to be turned into a three-dimensional piece of art.

“I feel extremely fortunate to be able to make sculpture full-time,” he says, “and I truly love what I do.”