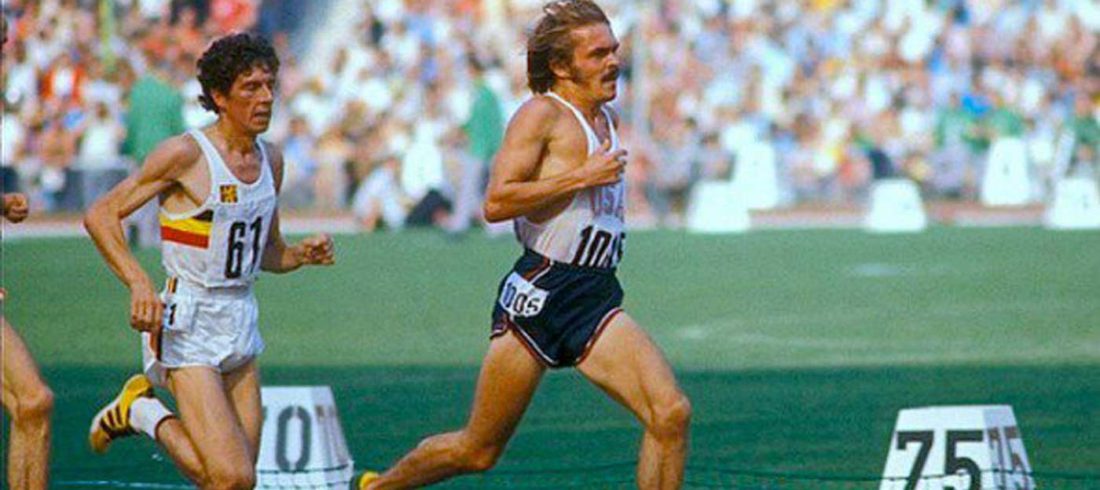

Want to see Bill Dellinger’s eyes light up? Mention his prize pupil, Steve Prefontaine. The 82-year-old former track distance coach at Thurston High School and University of Oregon, and Pre’s personal coach, eagerly escorts a guest into the den of his Hendricks Park home. Among impressive wall memorabilia, he points to a dramatic newspaper photo. It’s classic Pre—long hair waving, big mustache, lunging to the finish line, winning a race, giving it his all.

“The crowds used to just go nuts,” recalls Pre’s fellow 1972 Olympian Mike Manley. “He electrified everybody in the stands. It was that special self-confidence he had.”

Manley, retired after 30 years teaching at North Eugene High School and now in grad school at UO, lives just down the hill from his former coach. He’s happy to introduce Dellinger and share Pre memories.

Before sitting down to reminiscence, Dellinger hurries his guests over to another picture on the wall—himself capturing the 5,000-meter bronze medal at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. What’s remarkable is the same steely, intense look on the faces of both athletes. In the mid-1950s, two decades before Pre, Dellinger was king of middle distance running.

You see right there, visually, on Dellinger’s wall how each shared a gritty determination to be the best. Dellinger became Bill Bowerman’s first assistant track coach at UO. He served in that capacity from 1967 to 1973, then as head coach until prostate cancer forced his retirement in 1998. In 1967 and 1969—Steve Prefontaine’s sophomore and senior high school years in Coos Bay—Bowerman dispatched Dellinger to start reeling in the precocious teen track sensation to the Ducks.

Since a stroke in 2000, Dellinger has been challenged in verbal communication. But with help from his grandson, Jack Buckner, and his good friend Manley, along with an effective habit of writing out the ends of sentences that he starts verbally, the former coach paints a vivid picture of those first meetings with Pre.

“He knew my reputation (as a former international track star and a drill sergeant–tough coach), and I knew about his talent,” Dellinger remembers. “Even back then he was extremely sure of himself, but I didn’t mind it.” Dellinger shakes his head to emphasize.

He remembers those 1967 and 1969 visits with the Marshfield High School track star (and Coos Bay radio DJ). “When he was a senior, I brought along a group of the best runners at UO,” Dellinger recalls. The report he got back when the group went out for a practice run was that Pre shot out ahead and called back at the UO track stars, ‘Am I going too fast for you?’”

Dellinger smiles: “Not bad for a high school kid, huh?”

Manley and Dellinger also laugh heartily remembering when Pre’s self-confidence sometimes took a U-turn.

Like at the ’72 Munich Olympics.

As usual, Pre boasted he’d win the 5,000 meters and predicted his last mile would be under four minutes, leaving everyone in his dust for a win.

In the newspapers, Lasse Virén (the eventual 5,000-meter gold medal winner) pointed out Pre’s brash prediction and mockingly told reporters that the UO superstar may not realize everyone else is going to run fast, too. Then, in the final, Pre, as he always did, ran to win rather than earn a medal, and having spent all his energy, finished just out of medal range as Britain’s Ian Stewart edged him out for the bronze.

Dellinger easily forgives such strategy misfires. He loves Pre’s will and determination, and sees him as a doppelganger of himself in a competitive athlete manner. He readily says: “I’d rather see him do it that way. Go for the win. That’s the way he was wired.” Despite Bowerman’s attempts to inject more sense of strategy into Pre’s pedal-to-the-metal approach, Dellinger grins and says there was no taming the beast.

That’s why Dellinger points to Pre as a deeply satisfying coaching experience. “I gave him hard workouts,” Dellinger says. “I wanted to play on that intensity in him. He never missed a practice. He embraced everything I gave him. He knew that if he followed the plan he’d be successful.”

A humbling experience

Steve Bence, 800-meter specialist, ran with Pre and double-dated with him when the two were at UO (his girlfriend and to-be wife, Mary, was a close friend of Pre’s girlfriend Mary Marckx). He says Pre’s unexpected washout in the 1972 Olympics “was a real humbling experience for him. We didn’t see much of him the rest of that summer. But after that he wasn’t as cocky anymore. He was much more approachable and friendly.”

“We became pretty good friends,” Bence remembers. “He reached out to me. He saw something in me he liked and tried to pull it out (running talent). I was conservative and quiet and he tried to get me more outgoing.” The ever-mischievous Dellinger initially introduced Bence to Pre as a student from Spain. Bence, born in Tennessee, was an Air Force brat who had just gotten back stateside after living with his parents in Spain and on U.S. military bases throughout Europe. Pre promptly complimented Bence for his excellent English, not realizing his coach’s joke.

Tears well up in Bence’s eyes as he recalls Pre’s last day before he died. Bence spent a lot of it with him.

That day, Thursday, May 29, when Pre was 24, he asked Bence, his roommate Mark Feig, and future Olympian Matt Centrowitz to come over to play cards with him before what turned out to be his final race. Pre used the occasion to encourage Bence on recent displays of running toughness and improvements. “He wanted to show me how I could do even better, so we set a time for Saturday morning to get together for a workout and go over strategy he thought would work for me,” Bence remembers.

Early Friday morning, Bence heard the news of Pre’s death on the radio. “I just turned numb,” he says.

Today, Bence is closing in on 40 years with Nike, one of only a handful nearing that milestone. He works in global manufacturing, which manages sourcing for Nike’s 700 factories worldwide.

A style like Muhammad Ali

Another close friend of Pre’s was Jeff Galloway; along with the late Geoff Hollister, the three of them formed an inseparable trio as young men. Galloway, who has a richly rewarding career as a keen observer and writer on the art and science of running, is CEO of Galloway Productions, headquartered in Atlanta, which offers an array of training programs and events. These days, Galloway is especially enamored with exciting research that shows how running actually rewrites brain circuits to produce better attitude and personal empowerment.

“He was a fascinating guy,” Galloway says of Pre. “He’d always talk strategy about his upcoming races when we did practice runs together,” the 10,000-meter runner in the 1972 Olympics recalls. “He was very frank, direct, and used plenty of four-letter words in predicting what he’d do to his competition. Just like Ali in the boxing ring. He’d tell the world what he planned to do in an upcoming race. He was one of those athletes who tapped into this, playing the winning scenario over and over in his mind to the point I think he could actually will his predictions to happen. Most times, like with Ali, those predictions came true.”

“I don’t think he knew much about Ali in this regard,” Galloway adds. “He simply discovered this power in himself.”

Galloway, who helped grease the skids when Pre wanted to become an official part of Nike, will never forget their happy get-together a week before his last race.

“He wanted to share something with me and was really excited,” Galloway remembers. “So Pre came over and very proudly gave me his brand new Nike business card. He had just been named national director of public affairs. I know how much he wanted to be a part of Nike in an official way, and I shared his joy.” It’s a card Galloway will never let out of his sight.

River Bank Trailer Park

Maybe the best view of Pre was had by Pat Tyson, his roommate from ’72 to ’73, when Pre bought a 36-foot singlewide trailer at the River Bank Trailer Park in the Glenwood area.

“Rent was $15 a month, and split that two ways it’s $7.50 a month, each. Not bad,” Tyson chuckles. “Actually, Pre wanted me for my record collection,” which amounted to about 100 albums, a lot of it soft like The Eagles, Seals and Crofts, and Cat Stevens, he adds. “We both liked mellow music and we were both clean freaks, so that made it work out well.”

Tyson recalls that Pre was an avid nature photographer and converted a shed next to the trailer into his dark room. “He’d always be out taking pictures.”

In those days, they also enjoyed going to The Paddock, a sports bar in southeast Eugene.

“He really liked the atmosphere and people,” Tyson says. “It was the personalities of Bee and the rest of the staff, the games, and friendly patrons.” Air hockey was Pre’s favorite game at the bar.

“Pre had plans to replicate The Paddock in his own way,” Tyson remembers. “He was going to start his own line of sports bars, to be named Sub Four, with pictures of local sub-four-minute milers, first near the UO, then Corvallis, Coos Bay, and Portland. If he had lived, I have no doubt he would have carried that out,” Pre’s roommate adds. “I would have been right there with him.”

Tyson’s most treasured keepsake of his famous trailer mate is a stack of 45s, hits of the ’60s and ’70s, that Pre gave him. “These were 45s he played on air during his DJ years in Coos Bay,” Tyson softly remembers.

Like Dellinger, Tyson has gone on to become a legendary coach in his own right as one of the nation’s best high school track distance instructors, and for the past eight years, doing the same at Gonzaga University.

Multifaceted Pre

There are a number of key Pre contemporaries around still. Here’s a few more peeks from a few who were part of the fabric of Pre’s universe.

One of the most interesting relationships is that between Pre and Paul Geis, a contemporary runner who transferred to UO from Rice and was almost as good as the Coos Bay superstar. At the time he was dubbed Pre’s heir apparent by the press. Geis is bugged to this day at the media’s depiction of him as Pre’s nemesis, his antagonist.

“When I came to Oregon, my goal was to beat him, not worship him,” Geis says point-blank. “There were a bunch of people around the UO who put Pre on a pedestal. I didn’t do that. Just because I aspired to beat someone as a competitor doesn’t make me a bad guy.”

Off the track, when competitive flames were non-existent, the two runners were buddies.

“We partied, chased girls, and drank together,” Geis says. The two even survived a summer in close quarters on the European track tour, living out of their suitcases for five weeks.

“I admired him as a fierce competitor,” Geis continues. “But from my point of view, he was not a smart runner. I mean really, why do you want to routinely tell your competition what your strategy is before you race them?”

Geis majored in business at UO and went on to earn an MBA at Stanford. His career these days is managing high-end client wealth portfolios back in his hometown of Houston. “It’s full-circle for me, my dad did this,” he says. It’s a long way in time and distance from Eugene, but track fans are appreciative of the spice he added to the Pre mix in the wild 1970s.

A final comment comes from Janet Heinonen, a contemporary of Pre and the wife of Tom Heinonen, the groundbreaking UO women’s track coach.

“We were the same age,” she says of Pre. “I was into journalism and interviewed him at my apartment in 1970. But he talked more about photography than track. He came across as a really thoughtful person.” Then, at a cross country race, she adds, “I saw him go way ahead and then moon everyone behind him.” Including her husband.

Ah, the wonderful, many faces of Pre.