The shipments arrived without fanfare. Indeed, only a few people knew what they contained or their ultimate purpose. There were sheets of steel, huge blocks of wood, yards of aluminum foil, and bags upon bags of cement. Eventually, tall blocks of basalt were added to the inventory. The materials were raw, simple things, but they were destined to be transformed into masterworks of art by six of the world’s most skilled modern sculptors, who gathered in Eugene for the Oregon International Sculpture Symposium of 1974.

Sculptor Jan Zach, a University of Oregon arts professor, came up with the concept. In an effort to increase local awareness of sculpture, Zach wanted to invite some of the most internationally renowned sculptors to Eugene, where they could create monumental works while the public watched. As part of the process, the sculptors would make presentations in which they shared their thoughts about their work and art in general. This would not be a convocation of unknowns––only the best would be invited. The event would––if it could be pulled off––bring great honor to Eugene in the art world.

Once Zach shared his dream, others quickly came on board, but there were significant challenges along the way. It took many months to secure the funding from public and private sources, some of which wanted censorship rights or control over too many aspects of the public art. These requests were rejected, and in a few cases cases, because censorship was not permitted, agencies refused to help fund the symposium. And selecting the right artists who would agree to participate under the condition that they work and teach in public. Thanks to committee chairwoman Hope Hughes Pressman, a legendary Eugene arts advocate, and a team of collaborators and volunteers, all the pieces eventually fell into place. Six world-renowned sculptors agreed to assemble in Eugene, and the symposium was set for June 15 to August 1, 1974.

After the opening reception, the serious work began. Depending on their media and the kind of equipment required, some of the artists worked in the open space of Alton Baker Park, some at the university, and others among the vocational education shops at Lane Community College.

Each day, the public could gather and watch the process. When the artists had a moment, they would answer questions or offer their own thoughts on how the project was going and what it all meant. Ultimately, they created works that have provided inspiration, reflection, and enjoyment for those people who have taken the time to consider and experience them in the decades since.

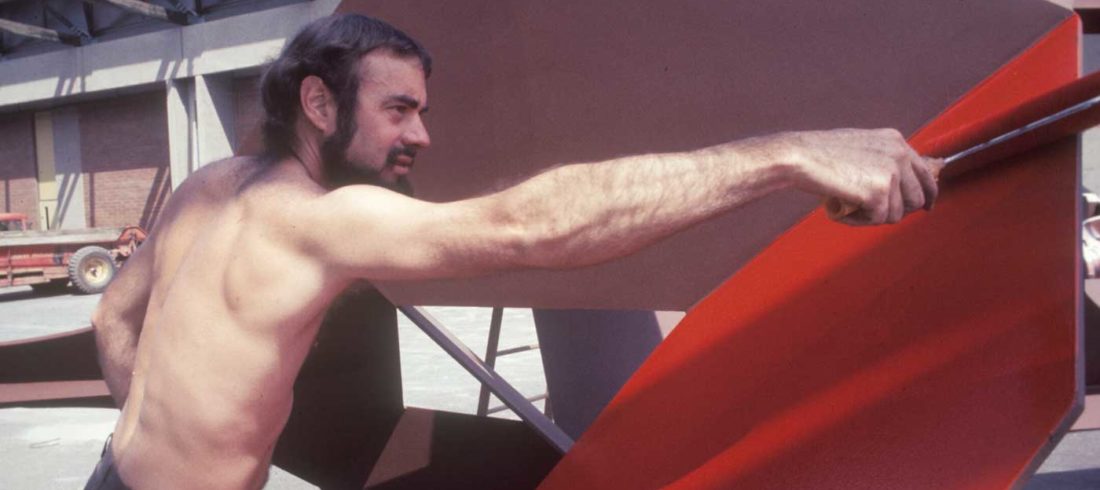

Bruce Beasley worked with welded steel. His piece, Big Red, can be found in Eugene’s Washington-Jefferson Park.

Roger Bolomey’s Cedar Temple went to Mt. Hood Community College in Gresham.

John Chamberlain’s painted aluminum foil treated with resin and dyes went to the University of Oregon’s art department.

Dimitri Hadzi’s basalt pillars went to the Lane County Public Services Building; they are currently in storage.

Bernard Rosenthal’s welded steel creation and Hugh Townley’s cement figures stand in Alton Baker Park.

As the event came to a close, it became clear that not only had the symposium resulted in six new works of art with public observation and educational opportunities from start to finish, it had also forged important new relationships between the arts community, educational institutions, and governmental agencies––putting Eugene on the international art map in the process. These relationships proved to be critically important, right up to the present day, as the community has again made a significant commitment to outdoor public art with its “20×21 EUG Mural Project,” which plans to add more than 20 murals by international artists to Eugene city walls by the time the 2021 IAAF World Championship track and field meet comes to town. Once again, the world will have its eyes on Eugene, and it will sparkle.