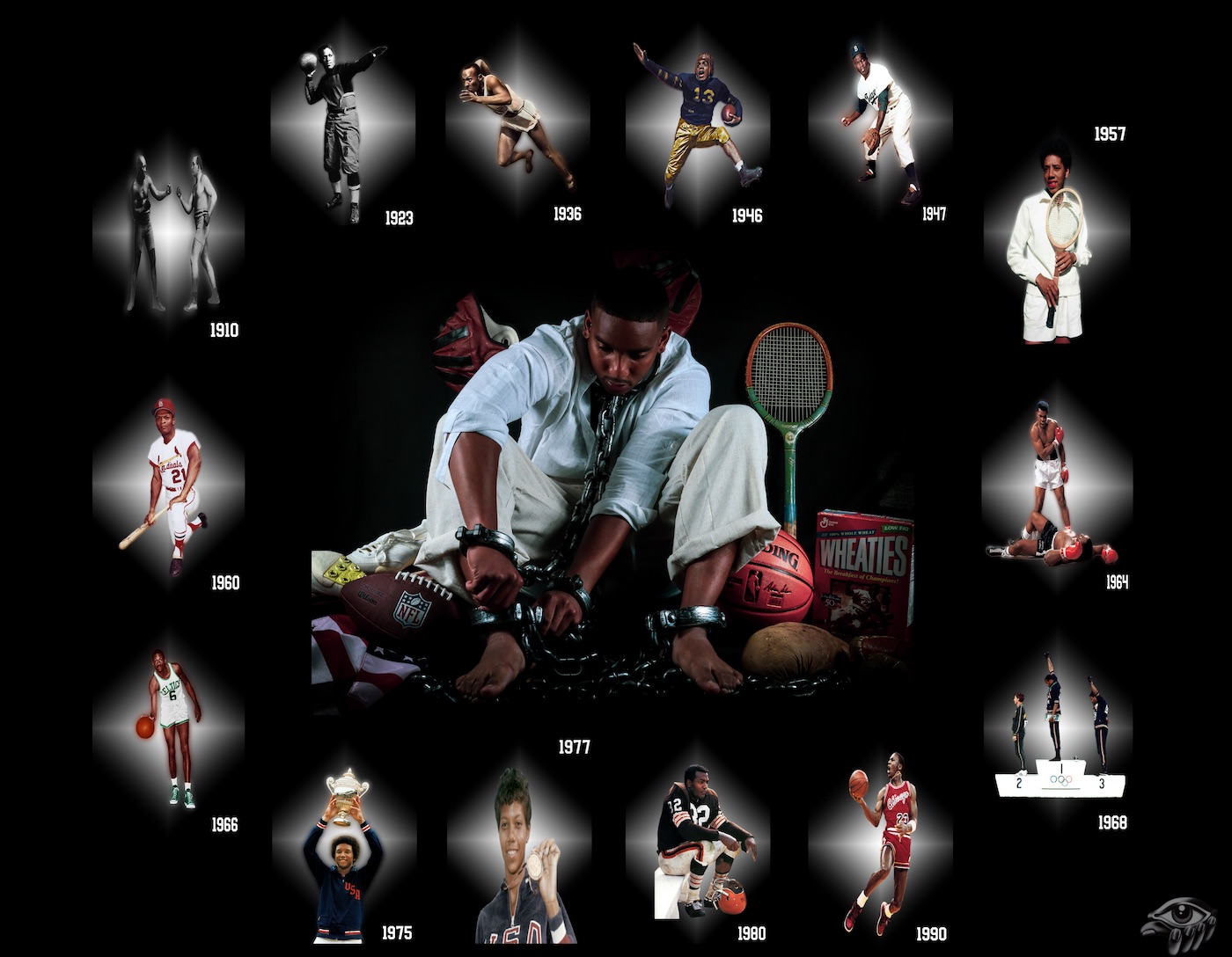

When you first walk into the Black Lives Matter Artist Grant Exhibit at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, you’re immediately met by two juxtaposed photography series. On your left are photos collected and shot by Malik Lovette, which depict Black athletes—including Lovette himself—in chains to illustrate their exploitation. On your right is a collection of photos that photographer John Adair took his family. The photos are stitched back together with gold, in the style of Kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery and making it more beautiful than it was before. These photos represent the racist damage members of his family have sustained, only to emerge stronger.

“The importance of this grant program and exhibition is the opportunity for artists of color to have a voice of their own,” says Lovette, who came to the University of Oregon on an athletic scholarship and studied painting and drawing as an undergraduate. “More importantly, being able to reflect, develop, create, and showcase their personal experiences with the world around them. Opportunities such as this can be pivotal for individuals that are pursuing creative careers, especially of color. It’s a building opportunity for all and I very much look forward to how this exhibition will play a part into each artist’s future. Overall, providing this sort of dynamic is overdue and much needed for the state of Oregon, the city of Eugene, and the institution itself (UO).”

Each piece from the 21 artists is equally thought-provoking and a reflection of our current times. Stunning sculptures and installations, watercolor portraits depicting local BLM leaders, collages, video, dance, more photography, layered textiles, pain, and emotion are all on display as part of this exhibition.

“There is a vitality and urgency to the works we’ll be presenting, and a wide range of moods, visual strategies, and voices,” said JSMA director John Weber in a statement. “We are gratified to be presenting these artists and this art as we continue long-term work to dismantle the legacies of white supremacy and create a more just society.”

The artists were chosen through a program funded by the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation that also extended to the Jordan Schnitzer museums at Portland State University and Washington State University. Artists in Oregon outside the Portland area were asked to submit to our local JSMA’s program, which were then judged by a panel to determine the winners of the $2,500 grants. The panel included Weber; Sabrina Madison-Cannon, dean of the UO School of Music and Dance; Jamar Bean, program advisor and director of the UO Multicultural Center; and assistant professor Jovencio de la Paz from the Department of Art.

“The importance of this grant, this exhibition, is that it promotes voices,” says Gabby Beauvais, whose introduction to her docuseries “Hear, I am” is on display. “It allows us creatives a space to share our thoughts on the current state of the country. It paves way for more conversation, community, and hopefully is an aide to continuing the fight for equality of Black and Brown skin in America. It gives smaller or even lesser known artists a platform to share their work, to be seen, and supported financially. Being supported financially as an artist, especially a Black female artist, is huge, especially when you are starting out and entering the ‘real world.’”

Here are some of the local grantees who are now on display:

While relatively new to the art scene, John Adair has always seen himself as a photographer, from documentary and photojournalism to portraiture. He quit his job as a semi-truck driver to follow his camera, letting the inspiration guide him.

“It’s been an extraordinary experience in being able to get to know my family on a far deeper level and to be able to express those stories through the resulting project, ‘BLK&GLD,’” Adair says. “Outside of myself, it is very important to get the message of Black American experience out there in all forms. A lot has been done to get the world to see that there’s more to us and there’s so much that can be gained and learned through creative expressions.”

Adair’s portraits of his family members seem to be torn, but glued back together with gold, similar to Kintsugi, a Japanese pottery practice that makes a broken piece more beautiful that it was before.

Gabby Beauvais has always been creative, drawing, writing, and expressing herself. As she got older, she started to understand the power of storytelling, especially in telling her own story. “The impact it has on other people, sharing your experience, your knowledge, even that you don’t know creates community, facilitates change, and bridges the gap between strangers,” she says. “Once I got a camera in hand, it was a wrap from there.” Now she uses videography, cinematography, and filmmaking to tell her and others’ stories.

“I’m a very observant individual,” Beauvais says. “Connection, interaction, messages/art with universal themes and other people’s ways of expression really allow me to cultivate my message (art) and confidently share it. . . . View the direction of my piece with an open mind, a willingness to listen, and not just hear the experiences voiced. Ultimately and actively remember that athletes are far more than the skill they present to an audience. Prepare to be a part of a movement of change to a system never intended for people with darker skin.”

A preview of Beauvais’ docuseries “Hear, I am: A conversation among athletes about the power of using your voice,” is available for view.

A transplant from New York, Kathleen Caprario has attended multiple artists residences and is widely exhibited, from which she draws much of her inspiration. She typically works with paint, layering different information to create a solid concept. She also works in a variety of digital and physical mediums.

“My work explores the intersection of physical place and cultural space through the open language of pattern and questions how I, as a white woman in America, can (re)locate myself in relationship to the histories and critical conversations surround racism, the environment, and privilege through my art,” Caprario says. “Through numerous iterations and missteps, I explore the opportunity inherent in its making and my own anti-racist efforts, each and every day as I consider the land and its complex social history to create a compression of time, a dialog between the past and present and a conversation for today.”

Her large installment, “Patterns of Privilege,” includes names of murdered BIPOC people and a mirror, among other imagery.

Sculptor Marina Hajek drew up in Guatemala during their Civil War, in a time when speaking out could be a death sentence. Sick of being silenced, Marina turned to art to express herself when she was able, something she was familiar with as her grandfather was an artist and archaeologist. After moving back to the US and through her studies, Hajek developed a love for sculpture in all forms.

“When I learned that this grant program was addressing Black Lives Matter and Marginalized Communities, I thought that it was an ideal way to support my project of the immigrant letters,” Hajek says. “My work addresses social issues. This project is about giving voice to the immigrant—it is time to hear the other side of the story about immigration. Immigrants have suffered of systemic racism, and this is what draws them to look for better opportunities elsewhere.”

Hajek’s project depicts three-dimensional face casts, with letters from immigrants written across them. She also has another sculpture, “El Grito,” on display.

California-born Malik Lovette came to the University of Oregon on an athletic scholarship, but his artistic talents showed themselves early in life. Focusing on the basics of painting and drawing as an undergrad led to the creation of many three-dimensional project during his time as a student and well acquainted him with JSMA. He will be returning to UO this fall as a graduate student to pursue a masters in architecture. He often works with mixed media, but seeks to find a balance between fine art and product design to develop his own creative process.

“What inspires me through my work is to inspire those around me to seek their passion, work towards their dreams, and find their purpose as an individual,” Lovette says. “But the notion of self-expression is the one thing that inspires me most because it’s one thing in life no one can take away from you! So, I utilize creative endeavors to express my vision of the world in hopes I’ve represented those that have come before me and able to serve those that will come after me. . . . Overall, this is a full circle moment for me and I can’t wait to showcase my artwork with the other great artists of this exhibition.”

Lovette’s collection of photos, “(Un)chained,” depicts Black athletes as exploited prisoners, still fighting for equal respect.

Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art Black Lives Matter Artist Grant Program

On display until November 21

JSMA | 1223 University of Oregon | 541/346-3027