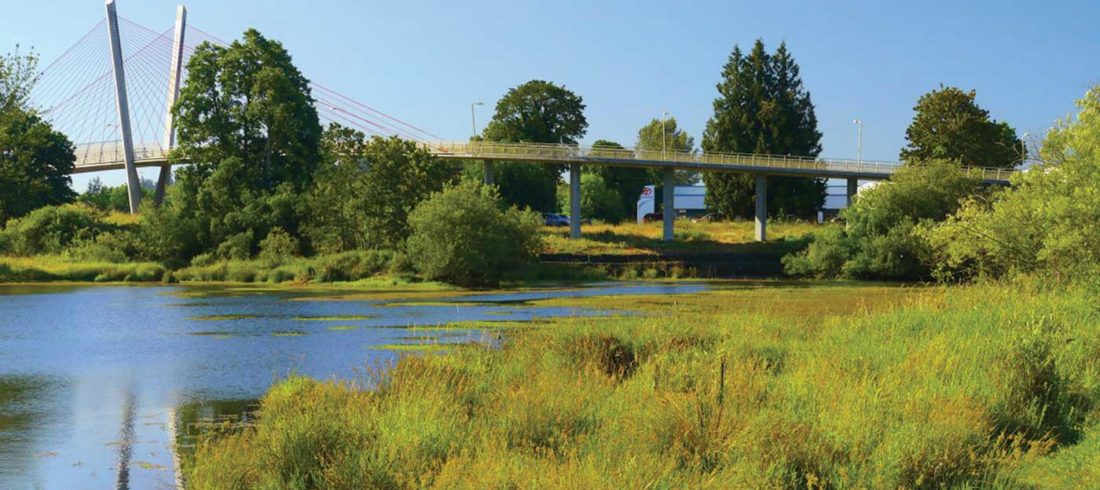

Two things characterize the Willamette Valley: clay soil and rain. These two elements work in tandem through the year to form the wetlands, particularly in areas around west Eugene, where both small spaces and vast prairies house plant life and wildlife unique to our region.

The annual cycle is what Diane Steeck, ecologist with the City of Eugene Parks and Open Spaces Division’s ecological services team, likes most about working in the wetlands. In the cold, rainy days of the Eugene winter, she says, there is hopeful activity in the wetlands, signs of a beautiful spring and summer to come. “From then on, it’s just changing every day,” she says. “You’re seeing new plants come up, you’re seeing new wildlife out there, you’re seeing baby birds and birds nesting, and just a tremendous amount of life out there.”

According to Steeck, the wetlands have historical as well as ecological significance. The first human inhabitants of the area, including the Kalapuyan people thousands of years ago, harnessed all the region’s resources for food and materials, particularly the camas that still grows in the area. To best take care of the area and preserve it, the wetlands were (and still are) periodically burned to clear out old thatch, keep trees from growing, and provide more light to growing plants. As a result, the plants in wetlands have evolved through fire and through the thick, clay mud that is present throughout the Willamette Valley.

Conservation efforts

Conserving these spaces first starts with reclaiming them. The city or Lane County purchases parcels, referred to as “prairie remnants,” that have often been farmed for decades. The previous owners may have rerouted water for irrigation, leveled the ground around the area, or, depending on what had been grown there, dramatically altered the soil. Steeck and her team go into these areas armed with heavy equipment to restore the hydrology and bring back the swells that once existed, place native logs reclaimed from other areas to provide shelter for the new inhabitants, and spread native seed to rebuild the natural plant and wildlife.

Steeck says that this can be a multi-year process. Not only does the construction take time, but it can be years before the plant life is established and diverse enough to best support the wildlife that will slowly recolonize the area. But to her, and for the community, it’s worth it.

“I think there are many, many benefits that the wetlands provide,” Steeck says, including “to citizens of Eugene, everything from flood control to clean water to wildlife habitat, places to go for human recreation to just enjoy the quiet and enjoy these big open spaces. So I guess for me, that whole range and also understanding our cultural history and preserving our cultural history and what’s been important to humans and human habitation on the landscape for the last 10,000 years.”

Your turn

The best way to enjoy the wetlands is to bike along the trail that starts at the Meadowlark Prairie, but there are many other ways to visit and learn, too. Steeck recommends visiting the Tsanchiifin trail, where a boardwalk takes visitors through the Willamette Daisy Meadow and to the Wetlands Education Center. You can also strap on your boots and visit the Gudu-kut Natural Area for a quick trip. Both of these are perfect for your kids, but also great opportunities for everyone to learn about the wetlands and their importance to this area.