We are all familiar with the phrase, “You are what you eat.” Another should be added to the lexicon: “You are what you breathe.” And while we have many choices about what we eat, the air we inhale is almost solely what the breeze blows in. Before I get to our summer wildfires*, backyard burning, and winter wood stove problems, I have a lot of good news. Many heavily polluted places now have the cleanest air they have seen since records have been kept. Los Angeles has gone from 150 days of ozone advisories in 1980 to fewer than half a dozen total over the last 20 years. London’s particulate pollution is 1% of what it was 100 years ago. We can make a huge difference by developing new technologies, establishing regulations, and applying them.

Locally, urban smoke pollution is way down. Sawdust furnaces were common — and smoky — in Oregon into the early 1970s. Open field burning for grass seed growers has dropped by 80% (although the chemical replacements for fire have other issues). Regulation has made a big and positive difference in our air quality. A quarter century ago, I was part of a committee that instituted the green/yellow/red wood stove burning advisories for home heating. That, and better stove technology, have greatly reduced emissions and particulate levels. Backyard burning prohibitions and regulations help stop smoke produced in one area from moving into another.

Globally, almost half the garbage generated by people is burned in open piles, and it is a major source of pollution in surrounding areas. Often, both plant waste and household waste are burned, resulting in a toxic stew of smoke and chemicals. While garbage burning is strictly forbidden here, people burning brush sometimes add prohibited materials. You can report illegal burning to LRAPA.

Two sources of air pollution are increasing, however, and only one is easy to control. Indoor air quality has gotten worse as houses have been better weatherized, and more plastic and manufactured wood products have become part of our everyday lives. Forty years ago my air pollution chemistry professor warned the class about the harmful pollutants released by gas stoves. While most newer models have an automatic ventilation fan, it only captures some of the harmful combustion products, and older stoves are an open flame in a confined space — something we have all been told to avoid. Just because the fire is blue, that doesn’t mean that all it produces is water and CO2.

The air in your home should be refreshed every two to three hours, much more often in the kitchen during cooking. Burning candles or incense produces the same lung-damaging particles as wood stoves and wildfires. An air to air heat exchanger can bring in fresh air without throwing away heat or, in the summer, already-cooled air.

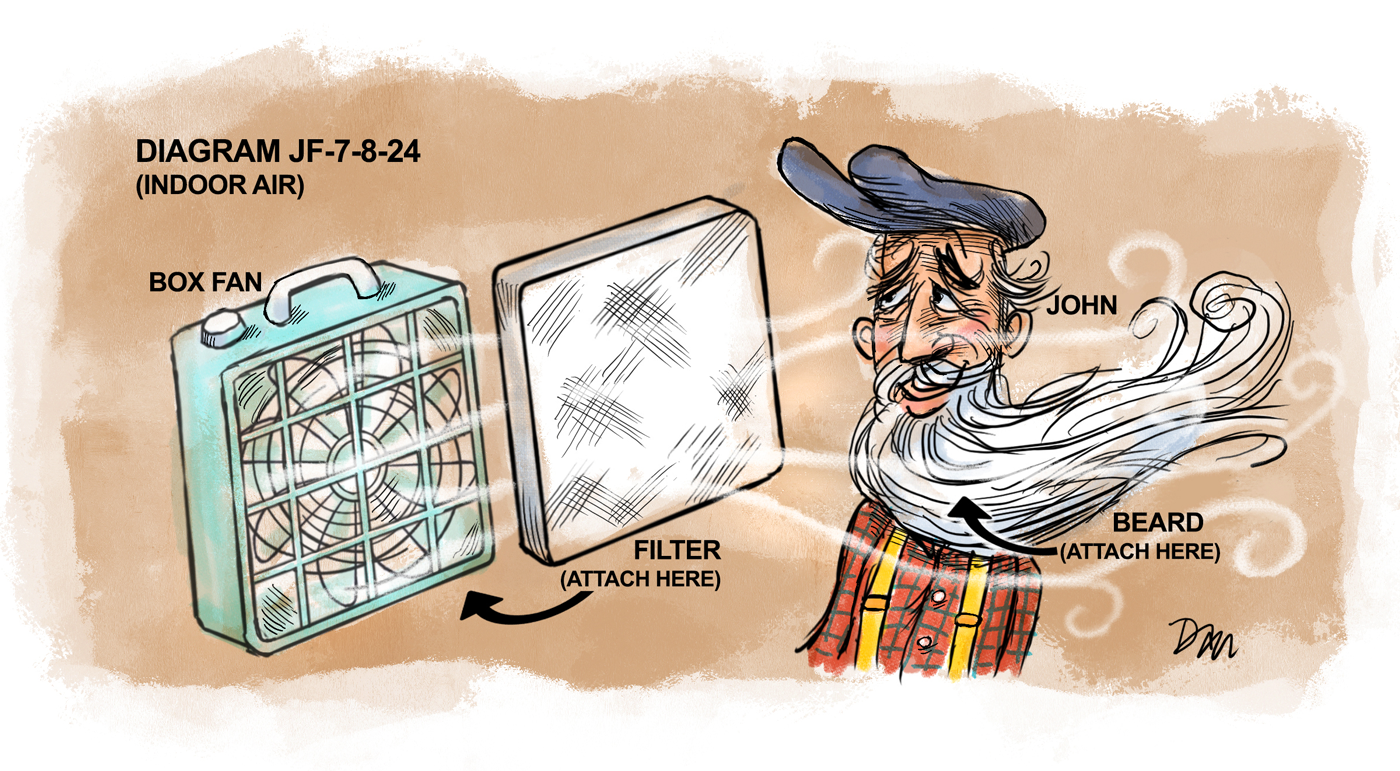

But the new pollution bully on the block pretty much does as it pleases. Wildfires are increasingly affecting our summers due to climate change and forest mismanagement. Warmer temperatures make fuels more combustible, and a century of fire suppression has left large fuel loads in forests that used to burn more regularly. While fine (tiny) particulate levels are usually lower inside the house during wildfires, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (or PAHs) can be higher inside because they come in from the fire smoke, and are produced by everyday living in the house. Your only recourse is some sort of filter system, from a whole house unit ($$$) to a box fan with filter paper on the front (cheap, and surprisingly effective). Monitoring air quality via purple air (purpleair.com) gives you real-time information that will let you make better choices about when to take a run, dry the laundry, or hunker down in the house by your filter fan.

*This study is about indoor versus outdoor air quality during wildfires specifically in Eugene: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov